No chemical protective clothing is comfortable to wear. Comfort is primarily governed by the air permeability of fabric, and fabric that is able to protect against harmful chemicals cannot realistically be breathable. It is the nature of the beast.

And yet, there are ways in which the comfort experienced when wearing a chemical suit can be maximized (or, at least, the discomfort minimized). This blog explains how.

Before looking at ways to improve the comfort of your hazmat suit, let’s consider why it is important.

Hazardous Chemicals in the Workplace

Many hazardous chemicals are harmful in very small quantities, so even tiny amounts of contamination that may not even be noticed must be prevented. So, suit fabrics are constructed of barrier films that prevent permeation of liquids but also inevitably prevent the passage of air. So, the reality is managing the comfort of a chemical suit is more about minimizing discomfort than maximizing comfort.

Yet doing so is worth the effort; enhancing comfort not only brings benefits but not bothering to do so may be a huge risk.

Comfort of Chemical Suits is both a Safety and a Productivity Issue

Comfortable PPE is commonly considered an expensive and unnecessary luxury – especially in the rigors of a demanding industrial environment.

However, the benefits of more comfortable PPE have been outlined in our blog here but are briefly summarized below: –

- Better work rates. Shorter and fewer rest breaks and overall, greater efficiency and productivity.

- More comfortable workers are more focused. This brings greater accuracy, fewer mistakes so fewer accidents, and reduced lost work hours.

- More comfortable workers are happier. They will have a more positive view of their work and employer. So complaints and problems will be fewer and staff turnover rates a lower (which reduces overhead)

So, the implications of achieving higher comfort levels for workers are clear.

Yet it is not only that increased comfort brings benefits. There are good reasons why failing to address uncomfortable PPE is a risk – with potentially disastrous consequences.

The Risks of Failing to Improve the Comfort of Chemical Suits

PPE that is uncomfortable is commonly not worn properly – especially in the case of chemical protective clothing. And if not worn properly it may not do what you need it to do: Protect Your People.

Walk into any factory and you will see workers taking risks with PPE; masks not worn over the mouth and nose properly, helmets removed in a risk area. There are many innovative ways workers find to gain a little more comfort from their suit: the hood not pulled over the head; the zip pulled partially down; rips torn in the back; even full coveralls worn as trousers with the sleeves tied around the waist as a belt!

The consequences for the business of harm befalling employees because of a failure to adequately protect them are considerable. Inquiries, the involvement of official bodies, fines for the company, and even possible legal action against managers, directors, and owners. A failure to protect the health of workers amounts to a failure to protect the health of the business.

Finally, of course, the discomfort of working in a chemical suit in warm areas can result in rapid heat exhaustion.

So, comfort is not just a luxury. An improved level of comfort means a greater likelihood of PPE being used properly, better protection, better productivity, and a reduced probability of accidents and all the consequences that go with them.

So, given that the natural state of most chemical suits is that they are uncomfortable to wear, let’s consider ways to reduce that discomfort.

How to Improve the Comfort of Your Chemical Suit

1. Improving Comfort Through Selection of Your Chemical Hazmat Clothing

Those selling PPE will recognize the negotiation that consists of two questions: –

“Is it certified to X standard?” and, “How much is it?”

In other words, users are often judging the suitability of PPE purely based on whether it meets the relevant standard(s), and with the next priority being cost. This ignores two truths: –

- Standards confirm PPE meets minimum performance requirements. Few applications in the real world require ONLY minimum performance.

- There are aspects of protective clothing that PPE standards do not measure or test. One of them is comfort.

So, as well as assessing a hazmat suit in terms of “does it meet the standard?”, it is a good idea to assess the factors that will contribute to better comfort and choose accordingly.

Fabric Properties of Your Hazmat Suit

Consider issues relating to:

Softness and flexibility

Some suits use fabric that has a distinctly “hard”, plastic feel. Garments made of better quality fabrics with better drape, are softer and more flexible will be less uncomfortable.

Noise generation

Those hard, plastic fabrics often also generate a high noise level when flexing. Not only is this uncomfortable it can also be a hazard by restricting hearing, making it easy to miss communication from colleagues, or the noise of moving vehicle hazards.

Ability to stretch

Softer fabrics also generally have more ability to stretch which helps with comfort and adds to durability and protection.

All these issues can be assessed with a simple visual and manual comparison of the different garment options available.

The Sizing and Design of Your Chemical Suit

Fabric usage is the largest part of the cost of a chemical suit, so the easiest way to reduce cost is to reduce the amount of fabric used to make it. The likely consequence however is a smaller garment.

Similarly, cheaper garments often use a simplistic pattern. Yet, (as suggested in the standard above) the design of chemical protective clothing is at least as important as the size.

Design elements that improve comfort such as those built into the Super-B style used for ChemMax hazmat suits can have an important effect on comfort.

2. Improving Comfort Through Better Understanding of Your Hazmat Suit Application

In mitigating workplace hazards, fear of the consequences of getting it wrong can result in overcompensation, providing more protection than needed. This not only affects your budget (you pay for more protection than you need), it also affects comfort. Users end up wearing garments that are bulkier, heavier, and less flexible than they could be.

Using EN Standards to understand your application

A better understanding of the different protection Types defined by EN standards can help guard against this. These Types are covered in detail here.

The differences between Types 5 and 6, and between Types 3 and 4 especially, are not well understood – a common source of over-protection. Understanding the differences and how they apply to your specific application might mean you are able to provide workers with the protection they need whilst also providing more comfort.

Types 5 & 6 Applications

However, note that only one of the three fabrics used for Type 5 & 6 garments is breathable, and so more comfortable. And yet many users that could use the breathable type use one of the other less breathable (and more expensive) options.

Type 5 & 6 users that fail to consider the breathable option are missing out on a much more comfortable experience.

Types 3 & 4

The detail of the differences between Type 3 and 4 has been covered in our blog here, but the key difference is indicated below: –

- Type 3: sprays a single pressurized jet of liquid at specific weak points on the garment, applying considerable pressure

- Type 4: sprays a wide shower-type spray from four nozzles, saturating the whole garment (which is on a rotating turntable) but applying little pressure.

Understanding the difference means that if you can identify that your application is Type 4 and not Type 3 (and our experience of the market suggests most applications are Type 4) you may be able to select more comfortable options, such as

- Cool Suits: garments designed for Type 4 protection that unlike any other Type 4 garments feature breathability derived from the design so are more comfortable.

- Two or three-piece ensembles. A jacket with a hood combined with trousers or a jacket with collar combined with trousers and a separate cape hood. This provides greater flexibility and better comfort.

So make sure you identify the type of liquid spray you need. It might allow choice of more comfortable options

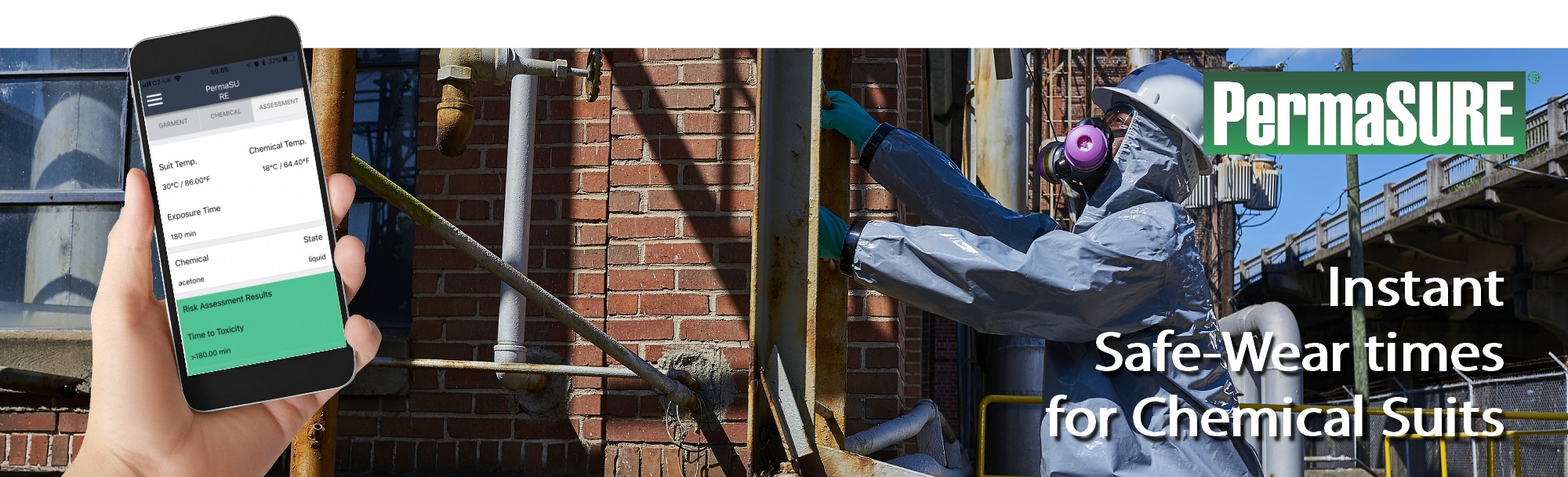

Understand the chemical, permeation, and safe-wear times.

The misunderstanding of permeation resistance test results and failure to assess how long a suit can be used safely against hazardous chemicals is dealt with in detail in our blogs here (understanding permeation test “breakthrough”) and here (How to calculate Safe-Wear Times), however, the key points are: –

- Proper understanding of the chemical, the hazards it presents and its toxicity will better inform the decision about how critical the protection is and how far it can be safely sacrificed in favour of comfort

- Proper understanding of permeation rates, cumulative permeation, and correct calculation of safe-wear times can help avoid paying for more protection than you need.

More accurate information means more targeted protection; effective calculation of “safe-wear” times (the time a suit can be safely worn before hazardous level of permeation may be reached) reduces the need to “over-compensate”, to build in unnecessarily wide safety margins by providing workers with much heavier protection than is needed.

3) Improving Comfort Through Task Management

Finally, whilst selection and proper understanding of the application will enable a choice of suit that may be less uncomfortable than others, no chemical suit can be truly described as comfortable. Thus, it may fall to better and innovative management of tasks to minimize discomfort further. In this, sometimes an innovative approach can be beneficial.

- Use of a two or three-piece ensemble may make it easier and less costly to remove the jacket for comfort during rest breaks.

- Consider using technology (such as air conditioning or dehumidifier units) to reduce temperature and humidity in work areas.

- Install regular re-hydration stations in work areas where possible.

- Increase the number and frequency of rest breaks.

- Ambient temperature will influence comfort level, so in warmer work areas, consider providing easily accessible air-conditioned rest rooms.

- In warmer climates, why not organize work so specific tasks can be conducted at cooler times of the day such as first thing in the morning?

CONCLUSION: The extra work involved in bringing about more comfort in your hazmat suit can bring benefits – including for the over-worked safety manager!

Whilst it is unavoidable that chemical hazmat suits are generally uncomfortable to wear, with some application it is possible to minimize discomfort through careful selection of the suit, better understanding of the hazard and application, and through innovative management of the task.

And while the benefits of achieving better comfort for a business can be considerable – including better productivity, lower costs, and a reduced likelihood of accidents (and all their legal ramifications) – for the safety manager who puts in the work to achieve it, the benefits will often be a more content workforce, fewer complaints about uncomfortable PPE, and less stress about whether PPE is being worn properly. In other words, it may require additional work to achieve more comfort, but it just might make life easier once you’ve achieved it!