You may not be familiar with the term “Risk Tolerance,” but we all recognize what it describes in our personal lives as well as our working lives. Risking passing that slow truck when you probably shouldn’t because you cannot be sure you can see far enough ahead; putting on your seatbelt after you’ve driven off to save a little time; crossing the road with your head buried in your Facebook page. It is natural to assume that if you’ve done it many times before without a problem, you can successfully do it many times more. Which, of course, may prove to be true. The trouble is it may also be the case that today is the day you don’t get away with it.

In a workplace where life-threatening hazards are commonplace, risk tolerance is a potentially serious problem of which the diligent safety manager should be aware. And in the case of chemical hazards in the workplace, the problem is even more acute. This blog looks at why that is the case and at how behavioral science can contribute to a health and safety plan to ensure it is addressed and that safety is maintained as the priority.

The Most Dangerous Words in PPE?

We are all susceptible to it; the tendency to grow familiar with risk, to pay it less and less attention over time, and to take diminishing care in mitigating it. And most of the time, we’ll get away with it and it’ll be OK. Until, of course, the day we don’t and it isn’t.

“It’ll be OK” must be a serious contender for prize of “most dangerous phrase in the safety industry.” Workers take what they consider to be minor risks every day. Removing safety goggles momentarily to wipe away sweat. Or perhaps leaving the coverall zip unfastened to allow a little cooling air inside. It happens every day, and any problems as a consequence are mercifully rare.

However, “rare” is not “never,” and it is a peculiarity of the way that probability works that:

- If there is a risk of an event, no matter how small is that risk, then all things being equal, that event will happen at some point.

- There is absolutely no difference in the probability that (again, all things being equal), the event will happen today, next year, or in ten years time. So if the probability is one in a million, the probability that it will happen the first or the millionth time is precisely the same.

So don’t make the mistake of thinking that one-in-a-million chance is essentially the same as never. In fact, quite the opposite; it means it will happen. And it’s just as likely to happen today as it is in ten years time.

Most Workplace Accidents Are Preventable

Research suggests that 99% of accidents are preventable. Which means that given different behavior by those involved, they would not happen. Similarly, “Industrial Accident Prevention” by W.H. Heinrich, first published in 1931, suggested that 88% of industrial accidents result from “unsafe acts.” Whatever the true statistics, it is undoubtedly the case that most incidents occur as a result of, or at least contributed to by, the behavior of those involved. It is, of course, impossible to know in just how many of those cases the words “it’ll be OK,” were uttered shortly before it happened, but it’s a safe bet that it was in at least a good portion of them. In other words, the perpetrator knew their behavior was unsafe but took the risk anyway.

|

|

The point is, maintaining a zero accident record is not just about providing workers with effective PPE. That is only part of the job. It is just as important, arguably even more important, to take positive action to ensure PPE is used or worn properly at all times. And because of the natural human tendency towards risk tolerance, that can only be achieved through an ongoing process of management of the people involved. Safety is not just a PPE management business; it’s a people management business too.

Why Handling Hazardous Materials in the Workplace is a Bigger Challenge Than Other Hazards.

Chemicals are a peculiar workplace hazard, unlike most. With most hazards, when an accident happens, it is very apparent and the consequences immediate. It would be difficult to not notice that a brick has just landed on your head, and the consequences will be immediately and probably painfully apparent. Similarly, if you fall from scaffolding, it is unlikely that you, or indeed your colleagues, would fail to notice, with the consequences being quite obvious immediately on reaching the ground. Meanwhile, you are also not likely to fail to notice a sudden flash fire in which you are engulfed, with the resulting burns making the consequences very apparent indeed.

Yet many chemicals do not work like this. Some, of course, do; acids that will burn, for instance. But often, not only is it the case that contamination by a chemical may not be noticed, but that the consequences of that contamination may not become apparent for months, years, or even decades later. In fact, there are four factors in the nature of many chemicals that make protection against them a unique challenge:

- The hazard may be unseen. Contamination of a worker can occur without anyone being aware of it. Yet, as a result, the chemical can be quietly absorbed into the body through the skin. (And, of course, this can be regularly repeated if the task is a regular requirement).

- Very small amounts of contamination can cause harm (dermal toxicity of chemicals is measured in micrograms). This is particularly the case if a small amount of contamination is being regularly repeated.

- The effects are often long-term. The consequences may not emerge for months, years, or even decades later.

- Those consequences may be catastrophic, life-changing, or even life-ending. The list of problems that can result from chemical contamination is long and sobering, including a range of cancers, damage to internal organs, damage to fertility or unborn children and so on.

| How much of a chemical is required to cause harm? |

|

The new system for classification of chemical suit fabric introduced in the in 2015 version of EN 14325 identifies three general levels of dermal toxicity:- 20µg cm2 High Toxicity These are also the toxicity thresholds used by the Lakeland Permasure® app for calculating safe-wear times. |

It is also worth noting that, given by some estimates, there are over 8000 chemicals in use globally on a daily basis, and with new chemicals being introduced regularly, it is inevitable that the consequences of contamination for many is only suspected or, even worse, not yet known. This can be confirmed by a quick browse of chemical safety data sheets where hazards are commonly listed as “suspected of causing cancer” or “may damage the unborn child” and so on. The fact is, a chemical can currently be considered relatively benign, with the harmful effects only becoming known in years to come. For this reason alone, when protecting against chemicals, assuming the worst and building in wide safety margins when it comes to contamination is a sensible policy.

The insidious nature of many “killer chemicals” means that the problem of risk tolerance is greater than with most hazards. Put simply, the hazards of falling from height are obvious, and consequently, workers are less likely to take those minor, risky, short cuts (although even with obvious hazards they do!). With chemicals, however, the hazard is not obvious at all; in fact a worker might well suffer regular, low-level contamination without even noticing it. And even if he is aware of it, there are no immediate effects, so the tendency over time to think “it’ll be ok” is much greater.

In other words, when it comes to managing people handling hazardous materials in the workplace, there is a much greater need to guard against the emergence of risk tolerance and an “It’ll be OK” approach.

The Usefulness of Behavioral Science

In simple terms, “Behavioral Science” is the study of human behavior. It endeavors to understand the innumerable factors that influence peoples actions. In layman’s terms, it might be described as an effort to understand “what makes people tick.”

For the safety manager considering how to mitigate the dangers presented by risk tolerance, putting some thought into “what makes people tick” can be very useful: –

- Why do people develop a blasé attitude to risks that could (or even “will” – think smoking) kill them?

- What are the barriers preventing them from retaining a high level of attention to safety issues over time?

- What methods can be used to break down those barriers and minimize the emergence of risk tolerance; in terms of chemical suits, to ensure they never relax their guard, never think “it’ll be ok”, and always wear chemical safety clothing correctly.

Having identified the reasons why workers develop risk tolerance and the barriers to behaving in a way to maximize protection and minimize risk, behavioral science provides a framework for developing policies and action to continuously “nudge” them in the right direction.

Why do workers develop a blasé attitude to risks?

As we’ve already stated, it is a natural instinct to grow familiar with risk over time. If it’s never happened before then, it seems a reasonable assumption that it will never happen. This is, of course, an entirely illogical assumption, but it is one to which we are all susceptible nevertheless.

We have also seen how the very nature of many chemicals (unseen, long-term consequences, and so on) means the risk of developing that blasé attitude is all the greater. Thus, the safety manager must be more aware of the risk and take more action to guard against it than with most hazards.

What are the barriers preventing workers from retaining a high attention to safety issues over time?

To add to the problems resulting in a natural tendency towards risk tolerance, there are also other factors that act as positive barriers to workers always behaving as they should when it comes to PPE. One of the greatest is discomfort, and again, in the case of chemical protection, it is arguably a greater issue than with other PPE.

Comfort Is a Safety Issue

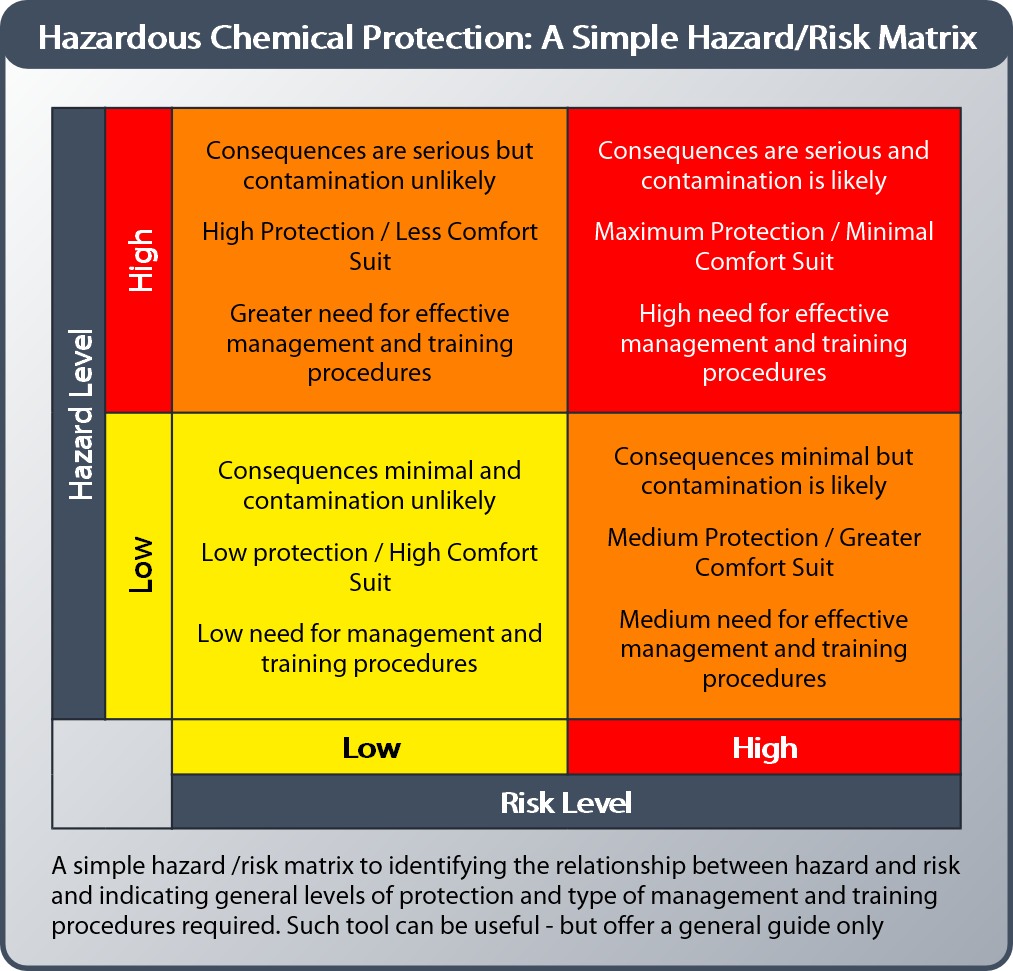

All PPE is a compromise between comfort and safety. Often the decisions as to where on the spectrum PPE sits between the two extremes is primarily determined by the level of danger the hazard presents. Where the danger is relatively small, greater emphasis can be placed on comfort. However, where the hazard is great; life-changing or life-threatening (as is the case with many chemicals), the priority must be protection and comfort is necessarily sacrificed. A simple hazard-risk matrix indicating in general terms the relationship between the hazard and the risk and its implications for the possible level of comfort allowable can be useful guide: –

In the case of protection against chemicals which will readily absorb through the skin anywhere on the body, and where dermal toxicity is measured in the tiny volumes of micrograms, a chemical suit must cover the whole body and resist PERMEATION, the inevitable process by which a chemical will pass through the garment fabric at a molecular level. Permeation is a different process to penetration as demonstrated by the video below.

It is important to understand that permeation is an inevitable process; it is only a case of when it happens and at what rate. So because chemical safety clothing must provide effective resistance even at this molecular level, it inevitably means garments are constructed with polymer film-based, non-breathable fabrics; a fabric which allows air through easily is unlikely to resist permeation of a chemical. And the greater the challenge of protection, the heavier and thicker is the barrier film. Often multiple films laminated together are used to provide the widest range of chemical protection. These garments are not only not breathable, they are often heavy and inflexible.

Meanwhile breathability, or air permeability of the fabric is, of course, the primary influence on comfort; the higher the breathability, the better the comfort.

The net consequence is that chemical suits are not comfortable to wear. Fabric technology, garment design, and management of the task can be beneficial, but the reality is, it is a case of reducing or minimizing the level of discomfort rather than actually making chemical suits comfortable. Wearing chemical safety clothing, by its nature, is a hot, sweaty and uncomfortable business.

The practical result for workers is an added incentive to take risks in order to gain a little comfort. In extreme cases, I have seen workers with holes torn in the back of coveralls to allow air inside the suit. More commonly, the front-fastening will be half unzipped, or the hood pulled down for the same reason. This is classic unsafe behavior. A typical example is shown in the image below of a worker disinfecting a bus taken in the early months of the Covid pandemic.

Leaving aside the fact that the mask is pulled down over the nose making it quite useless, the coverall is partially unzipped leaving the neck exposed. This might seem harmless (the worker might well have thought “It’ll be OK”!), yet if there are contaminated particles or droplets in the air they may settle on the exposed clothing at the neck where the worker will almost certainly touch later and then transfer to her face.

This is a classic, real case of seemingly harmless behavior that could prove disastrous. However, it is also very common behavior!

How Can You Guard Against the Tendency to Risk Tolerance?

This is where understanding of behavioral science plays a part. There are two distinct strategies that can be exploited, both of which have a place in a safety management plan.

1. Encourage and remind workers to always wear garments correctly and make efforts to minimise discomfort

The importance of a well-considered and effective donning process is critical, with regular review and ongoing training to reinforce as important as actually establishing it in the first place. Training should include the importance of ensuring garments are correctly worn at all times in critical areas. This subject has been covered in our blog here.

In addition, the written donning (and doffing) process should be well displayed on posters in the donning area. This will help support the message. And revising those posters on a regular basis can be useful; a poster that remains the same month after month will increasingly be ignored.; changing it regularly will ensure attention is paid to it.

Whilst chemical safety clothing is intrinsically uncomfortable, selection of more ergonomically designed suits, or where the hazard and risk allows, specialized versions such as Cool Suits can make a positive contribution. In addition, the task and its environment can be re-thought with comfort in mind. For example, reducing gaps between rest periods, providing frequent re-hydration opportunities, enabling “safe-rooms” or areas where a suit can be partially and safely removed for a brief respite, can all help in minimizing the probability that workers will take unsafe risks in the critical area.

|

|

There is space for being innovative in this area; for example, could a task be re-organized so that it is only performed at cooler times of the day? The point is any action to reduce discomfort can have a positive effect. No single action will provide the whole answer, but anything that contributes is at least worth the consideration of a cost-benefit analysis.

Apart from the benefits of reducing risk, there are clear benefits from improving comfort for a business’s bottom line. Find out more here. |

2. Ensure and refresh workers’ understanding of the risk, the hazard and perhaps most importantly, its consequences

Workers who have a full understanding of the risk of contamination where short-cuts are taken, of the hazards the chemicals present, the catastrophic illnesses it can cause, and the fact that those illnesses may only be apparent in the long-term, are less likely to take those small risks that might tempt fate.

Of course, this must be balanced. It would be of little benefit to frighten staff about the possible consequences of the chemicals they are working with to the extent that they are reluctant or nervous to do the work, but understanding of the hazard and the nature of the chemical, again with regular reminders, perhaps in the form of posters in the work area, can only contribute in minimizing the probability that they indulge in unsafe behavior and take risks with PPE.

3. Train, Train… and Train Again

I recall being told many years ago in a training course that in most situations, and all things being equal, when you give any training presentation, if people remember ten-percent of what you tell them then you have done a good job. (If true then the implication is that it is worth ensuring that the ten-percent they do remember is worth remembering!).

Training is a vital part of managing the behavior of staff when it comes to safety, but as a one-off exercise, it is largely a waste of time. Again, this is especially the case with chemical protection, where discomfort is common and, because of the reasons detailed above, there is inevitably a high tendency to think “It’ll be ok”.

Training must be an ongoing process with regular reinforcing sessions and periodic review. Don’t always repeat the training in the same way; the law of diminishing returns will inevitably apply; people just stop listening to the same message delivered in the same way over and over again.

- Regularly change the method and format of training to ensure people keep listening and keep getting the message

- Consider involving the workers themselves in organizing, structuring, and undertaking the training. There is no better way to understand a subject than to be required to train others in it.

- Manufacturers of the PPE involved might be made use of in providing training and supporting the message

- And reinforce training with coordinated, secondary messages. For example, posters around the work area reminding staff of particular aspects of the message and the dangers presented by the chemical, or perhaps e-mails or memos to staff with short, specific, reminder messages.

4. Be Innovative

In the same way that people grow accustomed to risk and pay less attention to it, they also grow familiar with the same message repeated in the same way; it will be increasingly ignored. And messages delivered in an unusual way or format will be noticed more, so changing the message and how it is delivered is not only beneficial, it can also help in maximizing its effectiveness. Like with addressing the problems presented by discomfort, there is plenty of scope for thinking well outside the box in this area.

Ideas could include:

- Involving workers own family in training sessions. If their partner understands the risks they face they are likely to reinforce the message on behalf of the company on a regular, daily basis. You could have a workers partner doing your work for you!

- Perhaps, if it can reasonably be organized, images of workers family in the donning area or in the workers PPE, with suitable, simple and direct messaging might be very powerful; a photo of a workers’ children with the words “Please come home safely, Daddy” on their PPE locker is bound to make a worker think twice about taking that risk.

- “Open days”, where workers and their families can view and inspect the PPE in use, perhaps with supplier or manufacturer representatives also attending to answer any questions, could again increase the likelihood that families will reinforce the message regularly.

Some of these ideas might seem a little over the top or even be unworkable for a variety of reasons. However, remember that the whole point of behavioural science is to consider ways in which guarding against minor unsafe behavior can be reinforced on an ongoing basis, continuously nudging workers towards a position where the never take those small risks that could have such grave consequences. Anything that can have a positive effect is worth consideration, and often it is the methods that seem most “out of the box” that are the most effective precisely because they are unusual. The unusual does tend to stick in people’s minds; the mundane does not.

The Battle for Health and Safety at Work You Can Never Win

Unfortunately, whilst there is plenty you can do to guard against the dangers of risk tolerance, it is a battle that is never over and that you can never entirely win. Preventing workers from developing an increasing tendency to take risks after uttering those dangerous words, “It’ll be OK,” and to tempt the “hunter fate,” is a never-ending process. Relax your guard, and it will rise again. It is the nature of the beast.

Yet, it is also a battle that you cannot afford to lose. Losing means someone may get hurt, and in the case of chemicals, the consequences can be not only catastrophic for those involved, they can be catastrophic for the business. If you doubt this, take a look at the movie Dark Waters, based on a true tale of what can happen when chemical contamination in a workplace occurs, and a case in which a smaller company than the one involved would almost certainly have been brought to its knees. The consequences of losing this battle, for both the people and the business involved, are almost unthinkable.

For this reason, when it comes to PPE and especially chemical protection, the programs you set up to manage the behavior of your staff must be ongoing and never-ending. There is no point at which you can sit back and think “job done.” Furthermore, it is no good trying to manage it in the same way over and over again. Inevitably the actions you take will bring diminishing returns. Successful management of risk tolerance is a task that not only will never end, it must be regularly reviewed, regularly revised, and constantly updated.

Managing the hazards of risk tolerance is undoubtedly a challenge, but with the right, long-term, innovative approach, whilst you can never win the battle, at least you will minimize the possibility that you will ever lose it.

Of course, the answer varies with different chemicals. However, what is clear is that many chemicals can be harmful in very small amounts. Dermal toxicity is measured in micrograms (µg), a microgram being one millionth, or 0.000001 of a gram.

Of course, the answer varies with different chemicals. However, what is clear is that many chemicals can be harmful in very small amounts. Dermal toxicity is measured in micrograms (µg), a microgram being one millionth, or 0.000001 of a gram.