When choosing a chemical suit, there is, not unreasonably, focus on how effectively the fabric resists permeation of the specific chemicals in use. This is assessed using the results of a permeation resistance test (though this test is often misunderstood – with potentially disastrous results).

However, less commonly considered is the construction of the chemical hazmat suit: not just the fabric but the seams, the design, and how effectively it connects with other PPE in use.

This blog looks at different seam types, garment construction, and design and how it contributes to a more effective safety plan for addressing chemical hazards in the workplace.

Too great a focus on chemical permeation resistance when selecting a chemical hazmat suit is understandable but could be misguided. As identified in our blog on key features to look for in your chemical suit, the most likely route of contamination for a chemical is not permeation through the fabric but penetration through weaknesses in the garment construction or through holes and gaps between the suit and other PPE.

Why Might Fabric Barrier be the Least Important Factor for Chemical Resistant Clothing?

Chemicals have no preference regarding which part of the body they permeate through your skin. They will take whatever opportunity presented and enter your body through the skin on your back, leg, face, or hands.

Not only that (and this especially applies to protection against dusts which float in the atmosphere and will move with air-flows), but chemicals will also always tend to take the easiest route of entry. Even if the barrier to permeation offered by the fabric is second to none, if there are holes or gaps in the garment construction a chemical will more readily and quickly penetrate through those rather than permeate through the fabric.

“Focusing on fabric permeation barrier and ignoring garment construction is a little like building a high garden fence to keep out burglars and then leaving the garden gate open. An intruder won’t bother trying to climb over the fence, |

And penetration generally deals with larger quantities of chemical, so is likely to be more critical. Thus, focusing on fabric permeation barrier and ignoring garment construction is a little like building a high garden fence to keep out burglars and then leaving the garden gate open. An intruder won’t bother climbing over the fence – they’ll just walk through the gate.

It is worth bearing in mind, the clear distinction between permeation and penetration. The key difference can be seen in the video below:-

This difference is important because whereas permeation deals with very small amounts of chemical, penetration can result in larger contaminating volumes, so problems with seams and construction can potentially have a more dramatic affect. You can read more about these processes in our blog here.

A further consideration is that even small holes can have a disproportionate effect because of two principles: the bellows effect in the case of dusts and of the process of “wicking” in the case of liquids. Also known as “capillary action,” this describes the physical process whereby a liquid is actively drawn through a small hole because of its surface tension. The result is that even though a hole might be very small – such as a stitch hole in a serged seam – the resulting volume of penetrated liquid could be considerable.

The combination of these factors means that seam construction and how chemical resistant clothing works with other PPE may be at least as – in fact, arguably more important than – the permeation barrier of the fabric.

What Types of Seams Are Available, and How Effective Are They in Terms of Chemical Safety?

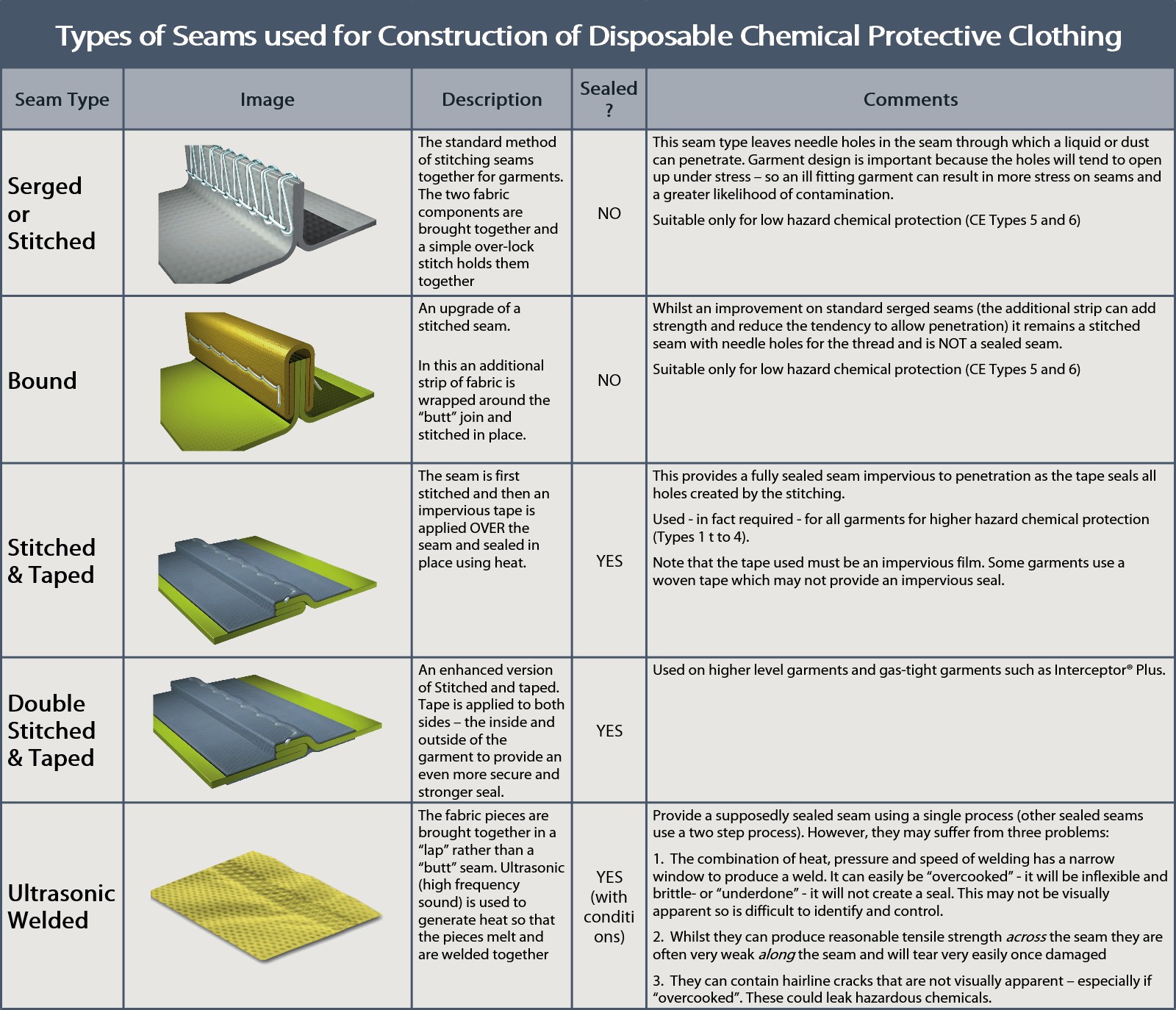

For limited life type chemical hazmat suits, there are five types of seam in use:

Of the seam types in use, the use of stitching and taping provides the best combination of a seam that is flexible and effective whilst maintaining an impervious seal. However, a stitched seam, whether a bound or a simple serged seam, is not sealed; it features stitch holes, which are likely to open under stress, (a problem made worse by a poorly fitting garment) and allow more ingress of liquids or dusts.

Thus, where an application features a liquid or particulate hazard that can be harmful in relatively small quantities, users should consider whether a garment with sealed seams (not stitched or bound) should be used.

Are sealed seams required by Protective Clothing Standards? |

European EN Standards In Europe, EN Type 5 and 6 garments can use serged or bound seams and pass the performance requirements provided those seams are of a reasonable quality and the garment is well designed. However, garments for Type 4 chemical protection and above require construction using some type of sealed seam. This is not expressly stated in the standards (EN 14605 for Type 3 and 4 and EN 943 for Type 1) but the requirements include permeation testing on a seam (“exposed in use”) for at least 1 chemical in Type 3 and 4 and 15 chemicals in EN 943 with a required performance of at least Class 1. Only a sealed seam could achieve this result, so by default, sealed seams are required. In addition, the Type Tests for Type 3 and 4 (described below) are such that a non-sealed seam is extremely unlikely to pass. North American Standards In North America, no such standards exist. The OSHA Protection Levels describe overall protection requirements with a focus on respiratory protection and make no specific demands on garment seam construction other than for the highest Level 1 which demands gas-tight protection and therefor indirectly specifies gas-tight, sealed seams. For lower levels 2 and 3 however, despite including protection against higher hazard chemicals, non-sealed seams could be included in selected PPE ensembles. This means users in North America may not make the critical distinction between sealed and non-sealed seams. You can read more about the differences between European and US PPE standards in our blog here. |

How is Seam Performance Measured for Chemical Resistant Protective Clothing?

Testing of Seam Strength

Strength of seams is measured by a simple tensile strength test which measures the force in Newtons to pull apart a seam in a 50mm wide sample of material.

The test is defined in EN13935-2 with the results classified according to the table in EN 14325:-

Seam Strength Classification according to EN 14325 |

|||

| Class 6 | > 500 N | Class 3 | > 75 N |

| Class 5 | > 300 N | Class 2 | > 50 N |

| Class 4 | > 125 N | Class 1 | . 30 N |

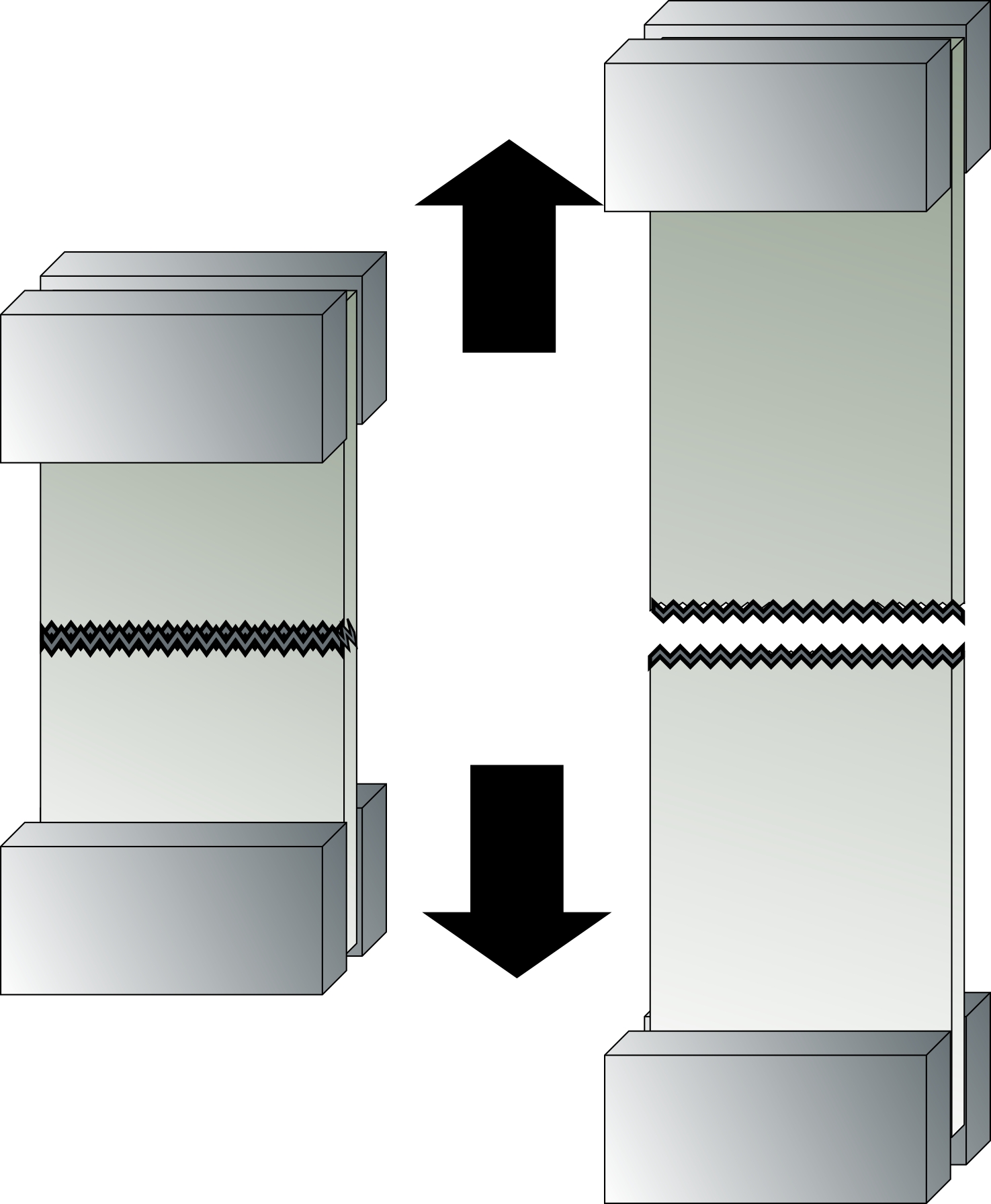

This allows comparison of the relative seam strength of different garments. However, be aware that this only measures transverse strength (across the seam) and not longitudinal strength (along the seam). This is important because ultrasonically welded seams may suffer from poor longitudinal strength, which is not measured by any test.

Testing of Seam Resistance to Permeation or Penetration

No specific test in standards for Type 5 and Type 6 garments measures penetration resistance of seams.

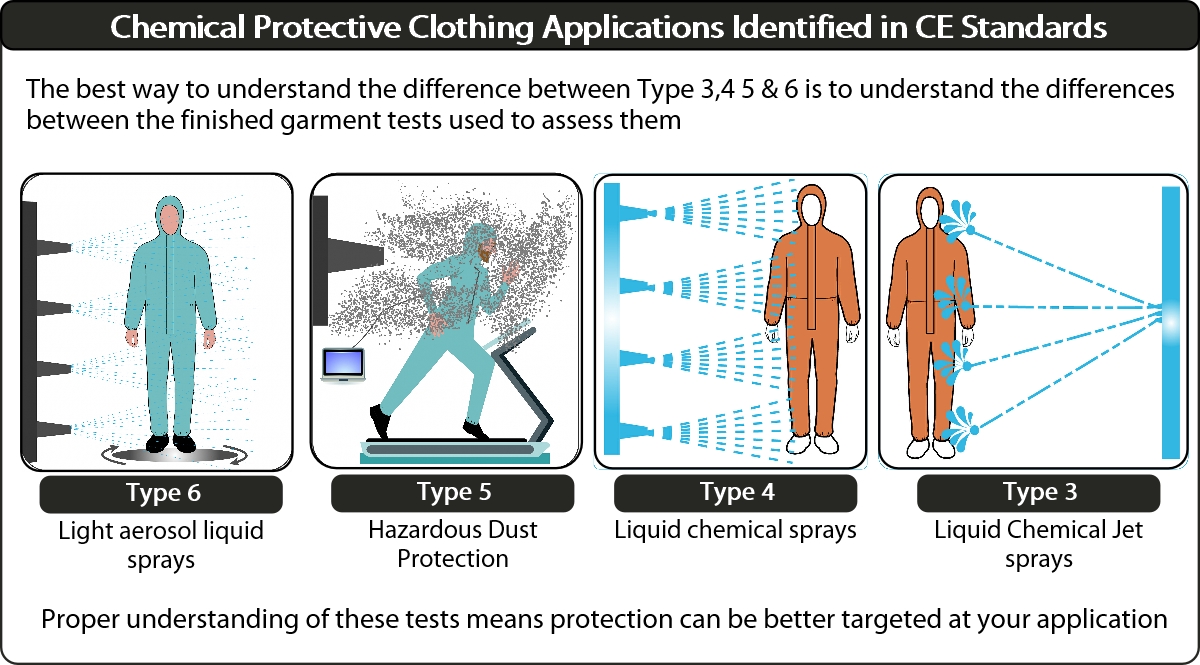

However, the finished garment Type Tests provide an assessment by default.

- A test subject wearing the garment enters a spray cabin and is sprayed with an aerosol spray, or in the case of Type 5, the cabin is filled with dust particles.

- Any seams that become damaged, or that open too much as a result of stress, would allow too much ingress of liquid or dust to allow the minimum performance requirements to be met.

- So in these tests any seam weakness would commonly result in failing the test (and pass is required for certification).

For garments of Types 4 to 1, the finished garment Type Tests would also result in a fail for any seams that are not sealed. In addition, the standards require permeation testing on a seam for at least one chemical with a result of at least Class 1.

You can read more about finished garment Type Tests here.

Conclusions Regarding Seam Types for Chemical Resistant Clothing Selection

- Of the types of seam available on limited life chemical resistant clothing, it is important to understand that serged and bound seams are not sealed. They feature stitch holes that can allow ingress and may open up more under stress. Garments with these types of seams should not be used for any chemical hazard that can be harmful in small quantities as some penetration may occur.

- Especially in the case of protection against infective agents, we always recommend garments with sealed seams (i.e. at least Type 4) to ensure there can be no penetration through pervious serged and bound seams – even though garments with serged or bound seams (Type 5 & 6) can be certified to EN 14126.

- Testing in CE certification does, by default, require certain types of seams (sealed for Type 1 to 4) and also requires that seams in all certified garments achieve a reasonable performance level. Poor seam construction will generally result in failing the finished garment Type Tests.

However, given the insidious nature of many chemical hazards, it is always worth giving consideration to seam construction. Even if a Type 5 or 6 garment is thought to be adequate, the question should always be asked;

“Are stitched seams good enough for the specific hazard and application?”

Both might offer good reasons to decide that a simple stitched seam garment is just not good enough, and that sealed seams is the only safe option.

An illustrative example of the importance of seam choice (regardless of EN “Type”) is where protection against asbestos dust is required. Not all asbestos applications are the same:

|

You can download a guide to garments for asbestos protection here.

What Other Elements of Construction and Design of Chemical Hazmat Clothing Might be Important?

Zipper or Front Fastening

A vital component of construction is the zipper and how it is sealed. The largest holes in garment construction through which liquids and dusts might penetrate are between the teeth in a zipper and the weave in its backing material, which is normally a woven polypropylene or polyester. (Proof of this is that close analysis of Type 5 testing shows that for most garments the majority of dust penetration is through the zip.)

Type 5 and 6 Garments

Often, such garments do not feature an ability to seal the flap. The detail of testing however shows that protection can be dramatically improved through the simple act of applying adhesive tape to the zip flap to seal that route of ingress.

Type 3 and 4 Garments

Most garments feature, as a minimum, a wide zip cover with wide double-sided adhesive tape, some feature a double flap system. Lakeland ChemMax® chemical suits feature a unique combination of features known as the “Super-B” style, including a double zip and double storm flap front fastening to ensure an effective and secure seal.

Type 1 Gas-Tight Garments

These garments invariably feature a gas-tight zipper so a simple flap covering the zip is sufficient to prevent major challenge by liquid chemical splashes. Lakeland Interceptor® Plus Type 1 garments feature a double flap with hook and loop fastening over the gas-tight zipper.

General Design and Sizing of Chemical Protective Clothing

The design and sizing of garments not only has a critical effect on the comfort of the wearer, it can also be vital in ensuring protection is maintained at the highest level during use in several ways:-

Comfort is a Safety Issue

Garments that are uncomfortable will commonly not be worn properly. If when the zip is pulled to the highest point under the neck it results in the hood and neckline uncomfortably tight, the wearer is unlikely to continue with it pulled to the point it should be. They will loosen it, in which case, the garment is not protecting properly

If the hood is poorly designed, restricts vision, or is too small, a wearer may not pull the hood up at all, so again, it is not protecting as it should. An improperly sized hood may also not move appropriately with the head, which could restrict the wearers vision resulting in other safety issues

Design Affects Durability

Producers of protective clothing – like all manufacturers – are motivated to reduce cost, and given fabric is a major component of cost, one of the best ways to do this is to reduce the fabric used by making the garment smaller. Another way is to reduce the other major component, labour cost, by making a more simple garment.

In the case of Type 5 & 6 garments with serged or bound seams, stress on those seams resulting from a poorly designed garment can result in an increased tendency for the seam holes to pull open, even if the seam apparently remains intact. This can easily result in increased penetration – especially in the case of dusts where the “Bellows Effect” might apply.

All Lakeland garments use a specially developed pattern and design including a unique combination of features to optimize the combination of protection, comfort and durability

What Other Considerations are Important for Safety Clothing?

Finally, regardless of the fabric properties, seam construction, and design features, if consideration of how a garment works with other PPE required is not addressed then the other issues may be academic.

A poor join between coverall sleeves and chemical gloves, or between hood and face masks could result in penetration – even if the coverall, fabric, and seams are the best available. As part of the process of selecting a chemical suit, consideration must be given to how well it works with other PPE and whether additional measures, such as taping up these joins, or seeking more specialist methods of creating a seal, such as a Push-lock glove connection system, might be appropriate.

The important point is that protection needs to be viewed in a holistic manner considering all required PPE and how effectively it works together.

CONCLUSION.

Managing Chemical Hazards in the Workplace: The Importance of Understanding, not just Knowing.

Clearly, whilst the barrier properties of the fabric used to construct chemical protective clothing is important, the type of seam used along with other design and construction elements can be at least as important. In fact, given that hazardous materials will always tend to take the easiest route of ingress inside a PPE ensemble, arguably they are even more important!

In addition, in the case of seam construction, whilst CE standards and Type Testing do provide some guarantees that appropriate seams are used on different garments (for example, a garment without sealed seams would fail the Type 3 & 4 Type Tests), it is always worth considering the details of the application and whether a standard garment and seam construction normally used is sufficient, such as in the example of asbestos protection given above.

In short, as is always the case with selection of PPE, it is not enough to simply ensure that it is certified. Users need to consider:

- The specific details of their application

- The nature and relative danger presented by the hazard

- The environmental factors

- The details of the relevant standards, what’s in them and what they tell you about the construction – including seam type – and protection provided.

Further, a holistic approach to the effectiveness of the entire PPE ensemble will contribute to ensuring workers are protected as they should be.