Recently I was asked to fill one of several speaking spots on the stand of a German partner distributor at the A+A safety show in Dusseldorf. Having agreed, it then became apparent it was three speaking spots, and the brief was: “How to encourage safe practices in the workplace”. Despite the short notice, I felt it was important to make a presentation that was both relevant and interesting.

I profess: I am not an expert on general safety practices.

My close to thirty years’ experience in safety is almost exclusive to chemical protective clothing, so, especially given the limited time I had to prepare, I decided I should revise the brief to a somewhat narrower field: “How to encourage safe practices when wearing chemical suits”.

(After all, it’s always wise in such circumstances to stick to what you know.)

I immediately realized that it’s a very relevant issue, chiming well with themes I have discussed in my published articles over the last few years. It’s so relevant, in fact, that I felt able to start the presentation with a bold statement:

“Encouraging and maintaining safe practices with chemical protection is more problematic than with most hazards”.

There are two key reasons why I would suggest this:

-

Possibly more than any other PPE, chemical suits are uncomfortable to wear.

Chemical suit fabric cannot be breathable; it must be an effective barrier to a whole range of nasty substances. If the fabric allows air to permeate through, it’s likely to allow those nasty substances through as well. Furthermore, chemical suits cover the whole body and may be sealed to other PPE, such as gloves or mask.

So chemical suits are uncomfortable to wear and there’s only so much that can be done about it, such as:

- using a Cool Suit

- using a better designed, more ergonomic suit (such as Lakeland’s “Super-B” style) or

- using a suit supplied with air for cooling purposes

But while these options are very worthwhile, realistically they are more about reducing discomfort rather than making a suit comfortable.

And the problem with any clothing that is uncomfortable is that people understandably do not want to wear it.

-

Any workplace may present safety managers with a several hazards to deal with: working at height, falling objects, flames, heat and, of course, hazardous chemicals.

It’s always useful to think about hazards in terms of whether they have an immediate effect or a long-term effect.

Many chemicals, however, are different and have no immediate effects (though not exclusively; some chemicals will cause immediate burns, for example).

Often, if chemicals come into contact with the skin, the worker will be entirely unaware of it. That chemical will be readily absorbed into the skin and he or she will have no idea. Moreover, if it’s a regular task, the worker could be coming into contact with that chemical every day and have no idea about the level of contamination. They’ll continue working, none-the-wiser, until the whole range of chronic, catastrophic and sometimes lethal health problems that can result from contact with hazardous chemicals start to become apparent.

But what sort of health problems? In presentations I like to use a real example: A plant in West Virginia became the center of a major incident in the early 1980’s when employees and locals began to develop serious health problems due to chemical contamination.

The chemical in question was known as “C8”, more accurately Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), used in the manufacture of Teflon®. Here is a short list of some of the long-term chronic health problems that this chemical can cause:

- Various cancers

- Liver disease

- Kidney disease

- Developmental problems

- Thyroid disease

- Birth deformities in children

Quite a catalog of catastrophic illnesses that, if they fail to kill, will certainly change the lives of those that succumb to them. And remember, such chemicals may have little or no immediate effect at the point when contamination occurs.

A brief look through the chemical’s safety data sheet (which comes with all chemicals) will advise on the types of long-term health problems it can cause. However, what makes this even worse is the fact that with so many chemicals, we simply do not know. Often, safety data sheets state things like: “suspected of causing cancer” or “may harm the unborn baby”, therefore the conclusion must be that the jury is still out on the effects of many chemicals.

With this considered, the consequences of certain chemical exposure may be unknown until the symptoms manifest years later.

So, in terms of establishing and maintaining safe work practices, chemical protection presents safety managers with a perfect storm:

- A hazard that may not be noticed if it occurs (i.e. when a worker is contaminated)

- A hazard that has no immediate effects – only long term ones – and they may be catastrophic

- A hazard for which the PPE to protect against is very uncomfortable to wear

As a result, this is why I believe chemical protection presents a greater problem when it comes to establishing and maintaining work practices. To make matters worse, these issues are further compounded when chemicals and breakthrough times for chemical suits are misunderstood.

Defining Permeation Breakthrough Time

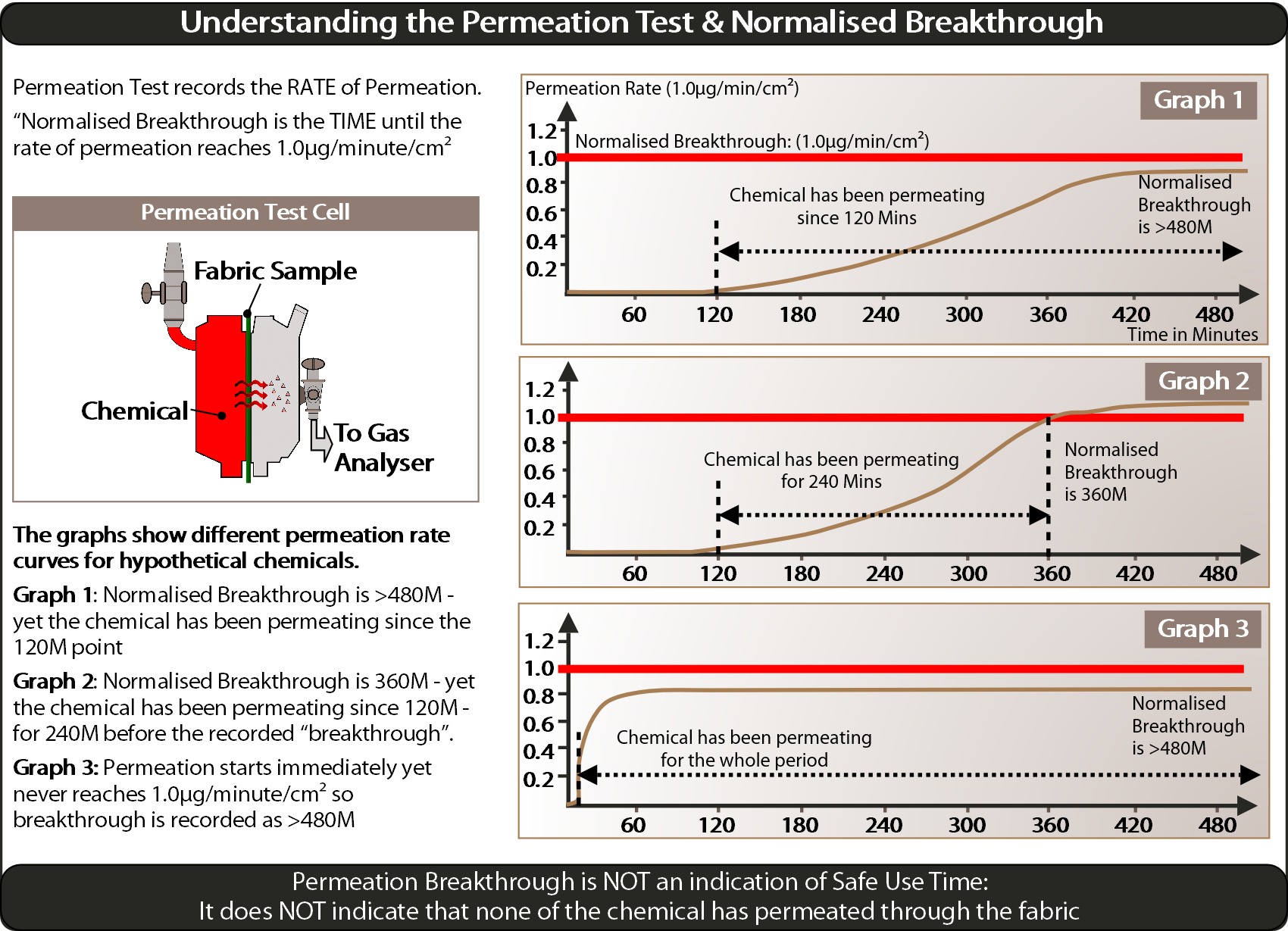

For those involved in the selection of chemical suits, the use of the “breakthrough time” to assess a suit is commonplace. Globally, users ask the manufacturer to supply this information, derived from a permeation test (in Europe, according to EN 6529). Often the result provided is > 480 minutes or Class 6 according to the classification in EN 14325.

Invariably, users believe this to mean that no breakthrough of the chemical was identified after 480 minutes. In other words, none of the chemical broke through the fabric in that time, so the suit can be safely worn for up to 480 minutes. It sounds logical, yet it is a complete misunderstanding of what “breakthrough” in the context of permeation testing means.

This has implications, as is shown by the graphs in the panel above, specifically in that the point at which the “first breakthrough” – the point at which the chemical is first identified to be coming through the fabric – can be well before that breakthrough time (it MUST be because the rate of permeation must start at zero and take time to reach the 1.0µg/min/cm2 rate at which the “normalized breakthrough”). This means that a substantial amount of the chemical may permeate through and contaminate the wearer long before the breakthrough time is reached.

Health Hazard Risks

So put these different elements together:

- Chemical suits are uncomfortable so it can be a challenge to ensure people wear them properly (especially as the danger is not immediately apparent).

- If a chemical comes into contact with a wearer he or she may not even notice.

- If it does, disastrous health consequences may not be apparent for months or even years later.

- In too many cases the possible consequences of chemical contact are simply not clear.

- Right now, the majority of chemical users throughout the world are using permeation test breakthrough as a safe-use time – a complete misunderstanding of what breakthrough means.

- Because of this misunderstanding, many users of chemical suits may be unknowingly contaminated by chemicals on a repeated basis, with no idea or appreciation of their safety

This may be happening in some cases. In others it may not. The fact is, in most cases we just don’t know. This is why the analysis of chemical suit safety practices are needed, to prevent future health problems before it’s too late.

How can hazard risks be prevented?

There are a lots of things that can be done in terms of safety practices – not least regular and repeated training for workers involved. Ensuring workers understand chemical hazards and recognize why chemical suits must be properly worn, will lay a foundation for any effective safety regime.

In the case of chemical protection specifically, there are ways to correctly calculate safe use times for chemical suits; the 2018 version of EN 14325 includes a new classification based on volume or mass permeated over time and the toxicity levels of the chemical.

On the other hand, Lakeland’s “Permasure®” smart-phone app provides a simple method of calculating such breakthrough times in the same way as the new EN classification, but also incorporates the effect of temperature.

The importance of understanding standards

In conclusion, it’s clear that because of the commonly invisible or delayed nature of the effects of chemicals, when it comes to ensuring and maintaining safe workplace practices, chemical protection presents greater challenges than many other, more obvious hazards.

This is yet another example of why, especially with chemical protection, users need to go much further than simply confirming PPE meets CE standards. They must also look into the details of standards and understand what it is telling them.

Failure to do so, and worse, making assumptions about what a standard indicates (such as that commonly made throughout the world about permeation testing and breakthrough times) can not only result in a failure to maintain safe workplace practices it can also, lead to a health time bomb being primed unknowingly.